The Marvelous World and Books of Arthur Tress

Arthur Tress has been taking pictures for more than five decades, constantly exploring new ways to express himself visually. From his early work in ethnographical photography, to environmentally-focused documentary work, and fantastical fabrications of “magical realism,” Tress has consistently reinvented himself. And he was kind enough to speak with us about his life, his work, and the books he self-publishes with Blurb.

Where are you drawing inspiration from currently?

I have a large collection of art and photography books that I read while eating or leave open to different pages around my house and studio and glance at during the day.

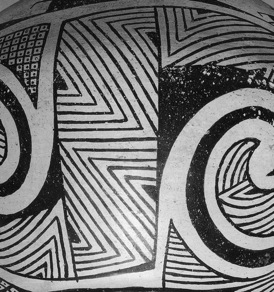

At this present moment, I am looking at the graphic work of Marc Chagall with all his dreamscape fantasy worlds of flying goats and cows. I’m also delving into a book of the mountain paintings of Marsden Hartley called Pinnacles and Pyramids, that relates to the series of landscape photographs I have been making of Morro Rock for the past few years. And lastly, I’m enjoying another book of large photographs of Southwest Indian ceramic pots from around the year 1200. It’s filled with swirling abstract geometrical designs in starkly alternating black and white zig zag patterns—it’s inspiring a lot of my newer photography which deals with unusual patterning found by the alternations of light and shadow.

What I am saying is, as I move to new ideas and pictorial explorations in my constantly evolving work, so do my scholarly investigations into the past, from where I continually borrow new visual ideas.

Inspiration does not really come in a flash to me but needs to be endlessly reinforced by learning how other artists over the centuries have explored many of the same pictorial ideas and challenges I am perusing and solved them with their own imaginative visual answers.

What’s it like seeing your work up in a place like San Francisco’s de Young Museum?

I was really pleased. The museum did an excellent job of framing, hanging, and lighting the show with excellent wall titles and labels and a full well-reproduced catalog by a prestigious art publisher.

They allowed me to be a part of all decisions about how things were displayed and how the book was edited. I got lucky and what more could any photographer want?

It ran concurrently with a large blockbuster exhibition of Jean Paul Gaultier that brought lots of crowds into the museum, and some actually drifted into my gallery space.

The gallery was always full of people actually looking at the pictures slowly and discussing them with their friends. They seemed intrigued and stimulated by the strange Tressian combination of the surreal within the documentary.

The Getty has recently acquired 85 of my vintage prints from the Appalachia and Dream Collector series, and that gives me a certain validation that I am glad to still be alive to appreciate.

It reinforced my feelings that a lifetime’s devotion to creating a disciplined body of work was a worthwhile endeavor. And, although the monetary rewards have been very small, the sense that I have actually made something wonderful and lasting gave me a great renewed pride in myself for having done all this alone and without much help for over 55 years.

It also made significant institutions aware that I was a photographer worth paying attention to and has attracted others to look seriously at my larger body of work.

Can you talk about the business side of photography? What has changed over the years and what has remained the same?

A friend of mine in San Francisco who was struggling as a freelance photographer just became the editor of a new start up magazine with a very high salary. So, while some areas of assignment have dried up, others are opening all the time.

Fine art photography areas are expanding with new galleries opening everywhere. And teaching opportunities have expanded as more schools and universities include visual expression using photography as a basis for a curriculum.

The way I survive is, to use the old phrase, “cobble together a living” from wedding photography, to stock photography, to selling archival pigment prints at your local frame shop around the corner.

Which is your favorite of the 20+ books you’ve done with Blurb?

I don’t have any special one. I have two or three that were done as special unique art projects and exist only as Blurb downloadable books such as Barcelona Unfolds or Colony. But I have been spending most of my energies creating a comprehensive Blurb book library of slim volumes pulled out of my organizing and scanning the several thousand vintage prints in my historic archive. These books include Egypt 1963, Caspar 1964, and Stockholm 1966.

I think that archiving in this way is a good idea for an older photographer. We all have bodies of work that have almost never been seen or had just a short lifespan in the public world of magazine publications.

By scanning the vintage prints and including letters and tear sheets from the actual published magazine articles, you can show how the images and texts were originally put forth into the world 40 or 50 years ago. This gives them much more clarity and meaning for today’s audience, rather than leaving them to be found in a lost box of random, bruised 8 x 10s in a dented Kodabromide paper cardboard box, lying forgotten in a damp storage area somewhere down in the basement.

I just sent 15 of these Blurb archive volumes to a publisher in Germany with the hope that it might make a worthwhile larger single retrospective publication of my lesser-known documentary photography from the ‘60s. Have not heard back from them yet though, but one keeps hoping and sending the stuff out.

Are you hopeful about the future of photography?

Yes. It is all about globalization now—everywhere there are dozens of photo festivals in Morocco, Singapore, Athens, South America, China, etc., giving emerging photographers a chance to display their fledging talents to the whole world via the use of blogs and newsletters.

Plus the rediscovery of forgotten photographic traditions and talents in these same countries is greatly expanding our narrow sense of our Euro/American-centric photographic history.

Plus the blooming of the indie book movement where, although bookstores are said to have died and that no one wants books anymore, is flourishing as collectors and institutions compete to buy signed limited-edition photo art publications.

Explore the wide range of photography books by Arthur Tress in the Blurb Bookstore.

This post doesn't have any comment. Be the first one!