The history of print

Every book is an achievement—the culmination of hard work to get new ideas on paper and out into the world. But the very existence of books represents a monumental accomplishment thousands of years in the making.

The progress of printing has driven the progress of, well, just about everything else since the first wooden blocks touched ink. So come along on this brief historical printing tour of how the books we love came to be, and you might find you appreciate them even more.

Types of printing

Woodblock printing

Early third century CE

While many civilizations devised some manner of pressing or rolling shapes and characters onto a surface, the history of printing as we know it began during the Han dynasty in China. The oldest remaining printed text is a copy of the Diamond Sutra, a Buddhist scripture dating back to 868 CE.

Artisans created these early printing presses by carving letters and artwork into wooden blocks in relief (standing out from the surface), which they then coated in ink. The ink was then transferred to fabric like silk (or relatively newly invented paper) by simply pressing down on the blocks.

It may sound like nothing more than a big upside-down stamp, which isn’t inaccurate. But this block printing process marked the first time people could reproduce identical copies of complex works on a relatively large scale. We’d call that a bit more important than a stamp.

Moveable type

1040

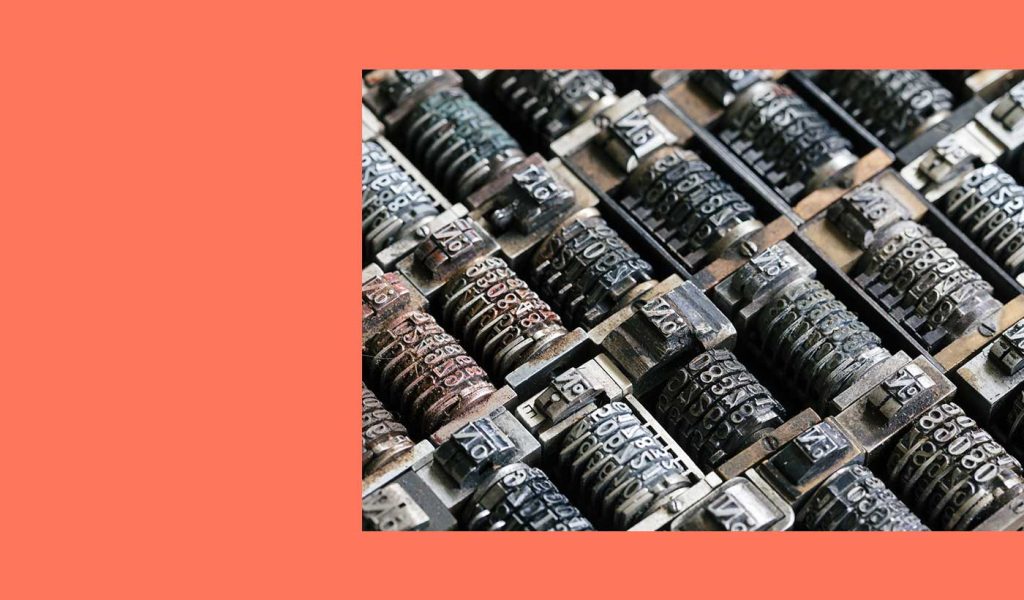

While Europeans wouldn’t fully embrace woodblock printing until the 1400s, the next significant step forward occurred in China centuries earlier. Inventor Bi Sheng’s movable type drastically reduced the material and effort required to prepare a single page for print. It did so by replacing the one-of-its-kind printing blocks with individual characters. Printers could use these blocks to arrange one page (the first use of typesetting), rearrange the next (the second use of typesetting), and finally reuse them for other pages and printed texts.

This modular approach also made correcting mistakes in a print far easier and less wasteful—so long as the type held up. The earliest movable type, made from soft or brittle wood, clay, or porcelain, wasn’t well suited to high-volume printing or frequent resetting. Interestingly, the first movable metal type (in this case, copper) wasn’t developed until the end of the 12th century. Using metal added the much-needed durability for printing frequently.

Printing press

1440

The trickle of technology into Europe led to perhaps the most well-known leap forward in printing. While a Korean Buddhist document named Jikji is the world’s oldest surviving book printed with movable metal type, Johannes Gutenberg developed improved methods for casting the type and introduced a self-contained movable type printing press.

Gutenberg’s press worked by inking the type and pressing it against a sheet of paper on a flat surface. The press design allowed bookmakers to make multiple copies quickly and precisely. His advances and the advantage of European languages requiring fewer characters resulted in the historic Print Revolution.

At a time in history when all the books in the world numbered in the tens of thousands, this first printing press began printing hundreds at a time. Suddenly, troves of knowledge that were once exclusive to the landed gentry and clergy fell into the hands of an increasingly literate public in the form of books, pamphlets, posters, and even printed music. The appetite for learning and the dissemination of ideas fueled the scientific enlightenment that would define the era—and ours.

Etching

Around 1515

While movable type made the printed word more accessible, complex images still needed to be drawn or painted and reproduced by hand. This laborious process hindered the printing industry. The process of etching (a type of printing that involves cutting a design into metal using acid) has been used since antiquity to mark or decorate ornaments and suits of armor. In the 16th century, artists adapted the process to create printing plates of their work that could be used hundreds of times without wearing out. Etching made a huge impact on the history of printing as this allowed mass-printed books to contain mass-produced artwork and for entire volumes of art to reach a wider audience.

We use etching to this day for some book illustrations. Plus, in another case of print changing our lives, tech companies use a modernized variant of the process to etch the circuit boards of whatever device you’re reading this on. (Unless you printed this blog out, thanks to the ubiquity of inkjet or laser printing, which are also coming up.)

Lithography

1796

Printed images took another step forward in the history of print with the invention of lithography. The process for this type of printing is like etching in that it uses acid, but the art is drawn onto a stone or metal plate using grease, and the acid creates water retaining or repelling surfaces for the lines. This simpler-for-the-artist process allowed for better accessibility, greater detail, and higher-volume art in print.

Everything turned kaleidoscopic in 1837, with the patenting of chromolithography, or lithography in color. By combining multiple meticulously aligned plates with separate inks, printers could reproduce near-perfect facsimiles of vibrant fine art—or get in on the golden age of poster design.

(And stay tuned because lithography isn’t just for pretty pictures.)

Rotary press

1843

The first regularly-printed newspapers appeared in the 16th century, thanks to Gutenberg’s movable type press. But it wasn’t until 1843 that The New York Sun made history by becoming the first paper printed on a rotary press.

The high-volume daily newspaper as we know it is the result of the rotary press, which replaced flat printing plates with cylindrical rollers and could print thousands of reasonably-priced issues every day. Of course, this step into modernity is also attributable to the industrialization of paper production and the proliferation of paper mills.

Offset printing

1875 (1904 for paper)

Offset printing is a type of printing that combines the oil-and-water chemistry of lithography with rotary printing and adds an extra layer of rubber (the “blanket”) between the print plates and the paper. Two significant printing advances, plus the inclusion of this then-novel material, enabled cheaper and faster production of plates, better control of ink, and generally sharper print results.

Most books you’ve read were likely offset-printed, which remains the most popular print method for mass-market publications today.

Screen printing

China 10th century CE, wider adoption 1910s

By the turn of the 20th century, the process of screen printing had been an artisanal practice for a thousand years. With this type of printing, artisans use mesh and stencils to transfer ink onto a surface when scraped with a blade—but this process was primarily limited to printing on textiles. It became far more popular when advances in chemistry allowed this process to be used on a much larger scale and on a wider array of surfaces, including on various types of paper.

Further innovations led to photo-imaged stencils so that nearly any color image could be screen printed onto almost any fabric. You probably have more than one T-shirt that unintentionally advertises your appreciation for how far screen printing technology has come.

Electrophotography

1948

In 1948 there was another innovative step taken in the history of print. The invention of electrophotography was a huge leap forward in several ways. This type of printing involves a dry photocopying technique that uses light and electric charges to transfer an original image onto a rotary-style print drum using dry ink (toner), which is then rolled onto another sheet of paper to make a near-exact copy.

If that sounds familiar, that’s because we also refer to this process as Xerography; the first commercially available Xerox photocopier brought the technology to the public in 1959. Anyone with access to the photocopier could reproduce any document without preparing special print plates, dealing with harsh chemicals, or battling messy inks.

Inkjet printing

1976

While many companies worked to advance a decades-old idea of propelling tiny droplets of ink onto paper, Hewlett-Packard was the first to offer this “inkjet” technology in a commercially available printer. Many others followed suit and developed their own methods to spray the ink. By the 1990s, inkjet printing was the most popular form of household printer. But the cost of the inks, and their tendency to degrade or clog delicate print nozzles, have seen that title move to the latest and greatest print technology.

Laser printing

1970s

Inventors applied principles of electrophotography to printing directly from digital sources in the 1970s, with the first “laser” printers. These were extremely expensive and primarily used in high-volume commercial applications, such as printing huge batches of individually numbered checks. As personal computers and desktop publishing software gained wider adoption, this type of printing made its way into many homes and offices in the 1980s, which also saw the development of color laser printing.

As you can see, the history of print has been impressive. Today, new iterations of laser printing have become so advanced that they can rival offset printing in volume and quality with a fraction of the setup cost. Systems like the HP Indigo digital printing press used by Blurb allow anyone to publish full-color books, one copy at a time or in runs of thousands.

Gutenberg would be flabbergasted.

Ready to create and print a book of your own? We offer many options including API Printing to make it easy!